I would like to thank Dr. Jonathan McLatchie for taking the time to review my presentation on the Synoptic Problem for Undesigned Coincidences and taking the time to write a reply. McLatchie is Assistant Professor of Biology at Sattler College, an experienced Christian writer, and a fine debater in the apologetics community.

First, I would like to correct some of the misconceptions McLatchie has about my presentation and my beliefs. I will also show how McLatchie has not taken seriously the concerns the Synoptic Problem poses for the subset of alleged inter-Synoptic Undesigned Coincidences. That was the purpose of my presentation and I left my own evaluation of the UCs aside. In this post I will go through each example and explain how the Synoptic Problem does pose a problem for the UC candidate. But, it seems that McLatchie’s response warrants an engagement with the merits of the UCs and so I will also engage with his defense of those examples. Last month, I provided a set of four criterion that should be used to evaluate the value of a possible UC: 1. Unique Material, 2. Natural Questioning, 3. Different Contexts, 4. Bidirectional vs. Unidirectional. I provided this set of criteria because I have not encountered a methodological explanation of what makes an alleged UC a good UC. Even L. McGrew notes (Hidden in Plain View, 20-21) that some UCs are stronger than others. I’ve read parts here and there and seen some of the McGrews’ explanations, but nothing formally methodological. Well, now those interested in this conversation can use (read: improve?) upon the criteria I’ve provided so we can continue to grow in our communal pursuit of truth. In case this post is too lengthy to follow, here is an outline:

- McLatchie’s Misconceptions

- Four Examples

- Pairing of the Disciples

- The Synoptic Problem

- Evaluation of the UC

- Herod’s Servants

- The Synoptic Problem

- Evaluation of the UC

- Woe to Bethsaida

- The Synoptic Problem

- Evaluation of the UC

- Ownership of a New Tomb

- The Synoptic Problem

- Evaluation of the UC

- Pairing of the Disciples

1. McLatchie’s Misconceptions

First, McLatchie says that I argue there are “no good examples of inter-synoptic undesigned coincidences….” This is not my position and not what I argued. I argued that such a conclusion is contingent upon one’s solution to the Synoptic Problem and source criticism.[1] My thesis was stated explicitly at 9:33 in my video: “I’ll be arguing that whether the alleged inter-Synoptic Undesigned Coincidences carry weight depends on the view of the priority and relationship between the Gospels, in conjunction with one’s view of source criticism.” I did say immediately following my thesis that “If you think that some of these examples are weak, you may be left with view few or, as I’ll argue, possibly no good examples.” That statement ought to be understood as conditional and qualified (“If”, “may,” “possibly”) and not as matter of fact of my own solution to the Synoptic Problem or whether the UC had merit. That the thesis of my presentation does not reflect my own personal solution should be recognized by my use of those conditional and qualified words. It very well could be the case that there are no good inter-Synoptic UCs, but it could also be the case that some good inter-Synoptic UCs exist. In fact, in my presentation I explicitly pointed out how Matthean priority provides stronger candidacy to the inter-Synoptic UCs.[2]

McLatchie also believes that I have overlooked the appearance of casualness in the text (“This is what drives many to assume that the evangelists had to have no knowledge of each other’s work before we can argue for an undesigned coincidence”). His evidence for that (inaccurate) conclusion about my view is my statement (14:55) that referred to Lydia McGrew’s example of separated crime scene eyewitnesses. Yet, my use of that example was not to argue that in order for UCs to work, there must be no dependence at all (to the best of my knowledge, L. McGrew does not defend the Independence view of the Gospels like David Farnell does in Three Views on the Origins of the Synoptic Gospels).[3] Rather, my point was that examples such as that, while helpful to demonstrate a UC in general, do a disservice to describing the way that at least two Gospels were composed.

Second, allow me to interact with McLatchie’s assessment of the four examples I looked it. Before jumping into that, I want to let the reader know that my intent in the presentation was to offer some logical possibilities (ones which I rejected as plausible in the presentation) and some more plausible solutions. This was done for the sake of thoroughness and exercise, but also because in at least one example, Lydia McGrew made a claim which was demonstrated to be an exaggeration: “cannot possibly be the result of design” (Hidden in Plain View, 88-89). Let the reader know that in that particular example, I rejected that possible solution in support of an alternative; this should have been an indicator to McLatchie that not all possible solutions are created equal. McLatchie is correct that possible solutions are not a refutation of the argument, if in fact those possible scenarios are more unlikely to have occurred than an undesigned coincidence. My interest in this sub-set of possible UCs is the absence of caution and careful analysis from some UC advocates as it pertains to incorporating the conundrums arising from the Synoptic Problem.

Okay, with those misconceptions corrected, let’s get to the examples. My reply will consist of first explaining how McLatchie misses the point of the Synoptic Problem concern and second in evaluating the alleged UC against the set of criteria I provided above.

2. Four Examples

A. Pairing of the Disciples – Matthew 10:1-4, Mark 6:7

i. Synoptic Problem: McLatchie’s responses to either of the two plausible solutions are wanting. For Markan priority, he says “the pairing of the twelve disciples in Matthew’s list does not explain anything in Mark, since Mark explicitly indicates that the disciples were sent out in pairs. What is there, then, for Matthew to explain?” The answer to that is simple: How the disciples were paired. He asks (again, rhetorically): “If Matthew was trying to enlighten his readers about whose partner was which among the twelve disciples, then why does he fail to mention that the disciples were sent out in pairs?” Matthew would not need to explicitly mention they were sent out in pairs in order for him to corroborate Mark’s details. A Designed Corroboration simply requires that the author makes a conscious decision to include a piece of information missing from the published Gospel he had read.[4] A cognitive thought by the author to include some missing piece of information from another Gospel negates the feature of undesignedness. Odd, it would be, if McLatchie were to suggest that for any independent information appearing in partially dependent narrative, that the author would have no inkling of a thought to provide that further information. This leads us to the Matthean priority scenario. If Matthew wrote first and Mark had a copy of Matthew, then perhaps Mark intentionally described to us how the disciples were sent out (since Matthew’s Gospel did not explicitly mention it). Interestingly enough, in setting up the situation for the reader, McLatchie writes, “Mark’s gospel however, fills in the missing detail ….” This is fascinating because on the Design Corroboration hypothesis, Mark does fill in the missing detail! But it is done so intentionally. So the DC advocate concurs with the wording of McLatchie’s remark! Except, in this case, McLatchie does not believe Mark intentionally “fills in” the missing information. He thinks “two-by-two” is not a summary of the parings by Mark. It would be a summary of the manner in which they were sent, assuming Mark seeks to briefly corroborate Matthew’s list. Indeed, Mark had already provided a list of names and to provide said list with the pairings in the style of Matthew would have been redundant. Additionally, McLatchie makes an accurate point that “there is no need” for Mark to summarize. But it was not argued that Mark needed to summarize; just that he did (or might have, more accurately stated).

ii. Evaluation: In my previous blog post I provided some criteria for what makes a good UC. In each of these examples I’ll run through those four criterion. First, there is unique material between Matthew and Mark, except in this case the unique material may not qualify as independent for the reasons I explained in my previous post and repeat now: There could be some editorializing by Matthew or Mark and that would make it a Design Corroboration.[5] Second, there does not appear to be a natural question that arises from these two passages, because no information is missing. A natural question arises when we would expect some information to be included and it is not (e.g. In Luke 23, Pilate finds no fault in a man who confesses to be a king). To this example’s credit, the question posed does not appear as forced as some other examples. So the type of questioning appears to be of moderate value. Third, this example fails to fit the criterion of different contexts. The two passages are about the same event (commissioning of the disciples) so there may have been some editorializing from either author. Fourth, this is a unidirectional UC. It is Mark who “fills in” the missing detail.

When the alleged UC is put to the standard, it is not the worst alleged UC but neither does it fit the bill. The pairing of the disciples seems like a weak example of a UC. Of course, if one were to believe Matthew and Mark were literarily independent of each other, that would change the game altogether and that would make this a stronger UC.

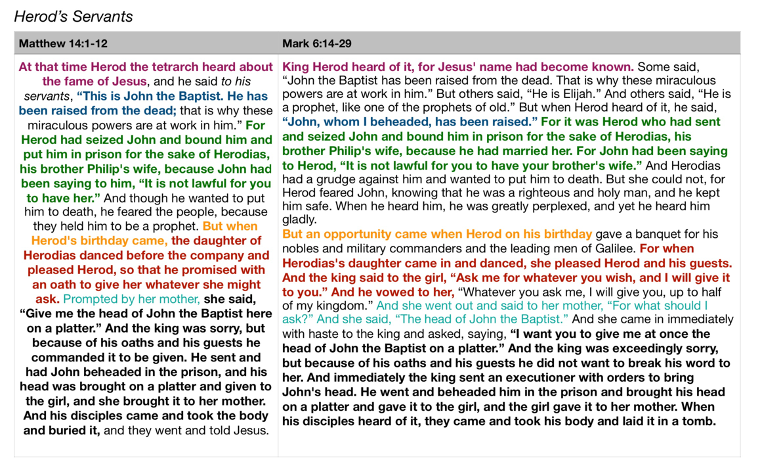

B. Herod’s Servants – Matthew 14:1, Luke 8:3

This is the strongest candidate of the four alleged inter-Synoptic UCs from my presentation.

i. Synoptic Problem: In the presentation I presented two plausible scenarios to the formulation of these passages that would defeat the notion of a Undesigned Coincidence. First, I noted that if the information came from Joanna in “a written account (notes) or simply were the source of an oral tradition” then Matthew could have provided the detail of the servants, but Mark (6:14-29) and Luke (9:7-9) redacted it. Here I do wish to retract the latter option, as mere oral tradition would be insufficient as a defeater for the concept of the UC. If, however, there were a written source containing both details, that would cause a problem of the UC. In difference to McLatchie, that written source would not need to include the listing of women who followed Jesus from Galilee. It would just have to mention that Joanna is the source of the content from Herod’s court.[6] The authors edit that detail out and there would only be the appearance of independence in the text (like how the blindfolding of Jesus example shows appearance of independence between Matthew and Luke, but once you include Mark, all of that gets tossed out). This plausible scenario (with admittedly no evidence) seems less likely than the preferred option: Matthew editorializes Mark 6:14-29. The proposal here is that, given Markan priority, Matthew transfers a statement from one person to Herod in order to compress the account.

In reply to this theory, McLatchie writes, “In Mark, then, it is ‘some’ who are saying that Jesus is John the Baptist raised from the dead. They are not the ones to whom it is being said. It seems like a stretch, therefore, to think that the reference to ‘some’ in Mark 6:14 would have caused Matthew to conjecture that Herod was talking at all, much less that he was having a conversation with his servants.” It is not a stretch if there are other examples in the Gospels where one author transfers a statement from one person and places it as if someone else had said it. For example, between Matthew and Luke, we have Matthew stating words in the Centurion’s mouth whereas in Luke the words are stated in the mouths of emissaries (Matthew 8:5-13, Luke 7:1-10). In this case, Matthew, knowing the true story, likely kept it simple by removing the emissaries from the narrative he knew.[7] Reportage model advocates like McLatchie do not like this sort of literary editorializing, and perhaps will opt to say that there is an error on the part of the author. In this case, maybe they would say that Matthew made an error because it was not Herod who said those things. I have no problem with an author seeking to shorten the story but being reliable in conveying the main points. We do this today when newspapers or tv reporters tell us what a politician said (when it may have been one of the staff members of the politician who wrote the press release). In this case, Matthew is removing some details but needs to retain the critical points of the story, so Matthew credits Herod for the important point which came out of Herod’s court.[8] You see Matthew’s use of compression of details and statements in this very pericope later on (“Prompted by her mother.” Cf. Mark’s description) and you also see Matthew’s compression of other Markan accounts elsewhere (e.g. Jairus’s daughter and the healing of the woman).

This understanding damages the merit of the alleged UC because Matthew no longer shows independent knowledge of the event (an event he very likely would not have been an eyewitness to). In this case, Luke’s throwaway remark supports what we see in Mark & Matthew (together), but does not support the independence of Matthew in this particular pericope.

The reason why the Synoptic Problem matters for this case is that it depends upon Markan priority. If Matthean priority were the case, it strengthens this UC candidate because Mark simply redacts the detail of the servants.[9] Hence my thesis is supported, to the benefit of the UC-advocate: “whether the alleged inter-Synoptic Undesigned Coincidences carry weight depends on the view of the priority and relationship between the Gospels, in conjunction with one’s view of source criticism.”

ii. Evaluation: 1. There is unique content in Luke (and Acts) about sources connected to Herod’s court. I’m skeptical that there is unique content in Matthew, as I explained above. If “to his servants” is an editorial remark that Matthew makes upon reading Mark’s narrative, then the air is sucked out of this alleged UC. 2. The type of questioning here does have value, “How does Matthew know what happened inside Herod’s court?” or more specifically, “How does Matthew know what Herod said to his servants?” These are good questions to come from the narrative as one reads it because we would not suspect there to be eyewitness testimony coming from behind enemy lines. 3. The material between Matthew and Luke comes from different contexts, but it seems plausible that Matthew’s material comes from Mark. 4. This is certainly unidirectional. Only Luke “fills in” the missing information.

This seems like a great case of a UC, but not without some concern. It’s a stronger case given Matthean priority (Matthew couldn’t editorialize Mark), and on that basis demonstrates the truthfulness of my thesis. Given Markan priority, it could be the case that Matthew is dependent upon Mark for this information and if that were the case, then it only shows that Mark and Luke have independent access on the happenings of Herod’s court.

C. Woe to Bethsaida – Matthew 11:21, Luke 9:10

First, McClatchie asks “How does Jaros account for this coincidence?” Notice in how he crafts the question about how I understand the alleged coincidence, McClatchie states it as fact that it is a coincidence. This is just begging the question of whether there is a coincidence in the text.

i. Synoptic Problem: McClatchie believes that Luke’s failure to mention the miracle at Chorazin is evidence against the possible Designed Corroboration (i.e., that Luke would intentionally add a city in a miracle narrative to corroborate the woe passage from Matthew): “Luke may have been expected to also think it worthwhile to mention what mighty works were done in Chorazin as well, though he does not.” How so? How does it follow that Luke leaving out a miracle from one city is evidence against the idea that he chooses to identify one city where a miracle occurred? Specifically, if Luke uses Matthew’s Gospel and wanted to include a miracle event from Bethsaida, an event which occurs in Matthew’s Gospel, then this would be a Designed Corroboration. If Luke intentionally added the city to enhance the details for the sake of thoroughness (since Matthew’s account of the miracle did not provide the location and Mark’s location is questionably in error), then it is no longer undesigned. If Matthew and Luke were dependent upon Q, the same problem arises about Matthew’s redaction of the location.[10] Or, in the very unlikely scenario of Matthew using Luke (Lukan priority), Mathew redacts the city out of Luke’s account of the feeding of the 5,000. Thus, the thesis stands: The Synoptic Problem does pose a concern for the alleged inter-Synoptic UC.

ii. Evaluation: First, in this case we have Luke mentioning the town where the feeding of the 5,000 occurred (Mark mentions the town as well, but apparently as the location where Jesus and the disciples were headed to after the miracle occurred). But, the pericope is not unique; in fact it occurs in all 4 Gospels. So if Luke used a written source for his information (e.g., Q 10:13),[11] then Luke’s material is not independent. Second, we have a forced question because there is no incomplete information directly related to the woe passages. If the UC advocate wants to say there is missing information here, then why would we not question all the missing information about Jesus not contained in the Gospels but even tangentially referenced. For example, why not ask who was it that Jesus saw on a walk between town A and town B? That seems to stretch the natural requirement of the questioning. Besides, we know from Matthew that Jesus’s ministry was based in Capernaum and it would be expected and reported that he traveled to towns to perform miracles. The end of Matthew 4 tells us that “Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people. News about him spread all over Syria,” and that “Large crowds from Galilee … followed him.” We do not need Luke to answer a question when the answer falls within Matthew’s purview. “‘Why did Jesus say that mighty works were done at Bethsaida?’”[12] Because according to Matthew, himself, Jesus lived in Capernaum and used it as a base of operations for his ministry in that region. Ah, but what if we tailored the question to make it appear as if information were missing? McClatchie, going for more specificity than McGrew states, “The question thus naturally arises what mighty wonders Jesus is referring to that occurred specifically in those towns of Galilee.” Here you can see how the question is not actually natural, but more forced because it already requires reformulation. Third, we can recognize that the woe passage and the feeding of the 5,000 are from different contexts, which decrease the chances of a Designed Corroboration. But as mentioned above, if Luke wanted to add the city to enhance Matthew’s or (correct?) Mark’s account of the miracle, then we have a Designed Corroboration.[13] Furthermore, if Matthew and Luke had a common source (e.g., Q) or if Matthew copied from Luke (unlikely), then Matthew could have left out the city of the miracle while Luke retains it. Thus, only the appearance of independence of the account. Fourth, this is unidirectional in scope, so not as strong as other UC candidates. Overall, I think this is a weak example of an Undesigned Coincidence.

D. Ownership of a New Tomb – Luke 23:53, Matthew 27:59-60

i. Synoptic Problem: Implicit in McLatchie’s response to me is his understanding that the Synoptic Problem does pose a concern for some UCs: “most scholars argue that Luke was written after Matthew, and so Matthew would not have had access to Luke, since it would not have been written at the time of his writing. And Mark, which predates Matthew (at least on the consensus view of Markian priority) does not mention the facts, provided by Luke and John, that the tomb was new and that nobody had previously been laid in it.” Here McLatchie recognizes that the order of the Gospels (and whether an author had access to other account(s)) would affect the value of the UC! To the particular case, the role that oral tradition plays in this scenario is Matthew’s intentionality in mentioning that the tomb belonged to Joseph, because that fact is not explicit in Mark (perhaps implicitly, though). So even if Matthew was “close up to the facts and are reporting either what they had seen and heard” on this point, his choice to include the detail would not have been undesigned. It’s possible to read Mark 15:42-47 as implicitly stating the tomb was Joseph’s. After all, what’s the likelihood that the guy who wants Jesus’s dead body would lay him in a tomb cut out of the rock that belonged to somebody else? And how would Joseph have access to a tomb that belongs to someone else? There could be some editorializing here by Matthew, given Markan priority. And, in the unlikely case of Lukan priority, Matthew could intentionally confirm a detail from Luke’s account, making it a Designed Corroboration. But, of course, if Matthean priority were the case, then this UC-candidate is strengthened because Matthew would do no editorializing. Hence, my thesis stands.

ii. Evaluation: There is unique content in Matthew (“own tomb”), but as mentioned above this could have been editorializing or a designed corroboration. 2. The question does arise naturally when reading Luke’s account alone. But if Luke used Matthew, and Luke redacts Matthew’s detail, then the organic questioning of Luke’s account loses its luster. This is a problem because … 3. The accounts are not different context, but about the same pericope. Finally, 4. This is unidirectional. I place this alleged UC as of more value than the Woe to Bethsaida, but still falling short of a credible candidate worth using to support the overall Argument from Undesigned Coincidences.

As we have seen in each of these four cases, McLatchie’s position fails to sufficiently consider the concerns that arise from the Synoptic Problem. I do want to thank him, again, for reviewing my presentation and for offering some remarks for all of us to consider in this Christian discussion.

If you have made it thus far, congratulations! This has been a lengthy, but important reply to explain how the Synoptic Problem does pose a problem for some alleged inter-Synoptic Undesigned Coincidences. Even if you do not agree with my evaluations of each of the candidates, I hope you’ll agree with me that the Synoptic Problem poses some concern that ought not be brushed aside so easily.[14]

If you want to support the work of this writing, teaching, and speaking ministry, you may begin your support at this link.

Footnotes (far superior to endnotes)

[1] For a description of Synoptic Problem, proposed solutions, and the value of source criticism in general, see Robert H. Stein, Studying the Synoptic Gospels: Origin and Interpretation, Second Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2001), 143-169. For a more succinct overview of source criticism, see Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of the New Testament. (Nashville, TN: B&H Academic, 2016), 29-34.

[2] Traditionally, it is believed, early Christians thought Matthew was the first written Gospel. For an interesting argument that the early Christians, specifically Papias, held that Mark was written before Matthew, see Robert H. Gundry, “The Apostolically Johannine Pre-Papian Tradition Concerning the Gospels of Mark and Matthew,” in The Old Is Better: New Testament Essays in Support of Traditional Interpretations (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2005; Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2010), 56.

[3] See also on the independence view, Robert Thomas and F. David Farnell, “The Synoptic Gospels in the Ancient Church” in The Jesus Crisis: The Inroads of Historical Criticism Into Evangelical Scholarship (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1998), 57-75; Thomas Edgar, “Source Criticism: The Two-Source Theory” in The Jesus Crisis, 132-153; For reasons to reject strict independence, see John Wenham, Redating Matthew, Mark & Luke: A Fresh Assault on the Synoptic Problem (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1992), 9-10.

[4] Grant Osborne suggests that Matthew was trying to, “stress the Deuteronomic demand for two witnesses (Deut 17:6, 19:15)” If Matthew was primarily writing to a Jewish audience, this would be a feature he would want to implicitly include, and that the audience would know they were in pairs. Osborne also thinks there is a “possible” allusion to Mk 6:7. See Grant Osborne, Matthew: Exegetical Commentary of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2010), 372; Blomberg similarly, though more cautiously, states that the pairings were, “perhaps … patterned after the law that required at least two witnesses (Deut 19:15).” Craig Blomberg, Matthew, vol. 22, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1992), 167. R.T. France opines that the first two groupings were paired because they were “brothers” while, “ the others apparently arbitrarily grouped for literary effect.” R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, The New International Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publication Co., 2007), 376.

[5] On different ways the Synoptic Gospel writers redacted their material, see D.A. Carson, Douglas Moo, and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1992), 38-41.

[6] D.A. Carson, here, suggests, “How the reports of Jesus’ ministry reached Herod is unknown; it may have been through Cuza (Luke 8:3),” (D. A. Carson, “Matthew,” in The Expositor’s Bible Commentary: Matthew, Mark, Luke, ed. Frank E. Gaebelein, vol. 8 (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 1984), 337).

[7] Leon Morris, Luke: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 3, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 157, prefers this solution, stating, “… it is better to see Matthew as abbreviating the story and leaving out details inessential to his purpose. What a man does through agents he may be said to do himself. So Matthew simply gives the gist of the centurion’s communication to Jesus, whereas Luke in greater detail gives the actual sequence of events.”

[8] Leon Morris concludes, “Matthew does not say who brought the report, but obviously any tetrarch would have sources of information about what went on in his region.” Morris goes on to say in a footnote, “ The definite article indicates ‘the’ news about Jesus; Herod heard the definitive story. The absence of the article with Ἰησοῦ is unusual in this Gospel.” Thus, if Morris is correct, we may safely infer that Herod heard about a widely circulated story. See Leon Morris, The Gospel according to Matthew, The Pillar New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI; Leicester, England: W.B. Eerdmans; Inter-Varsity Press, 1992), 369, n.3. If Mark and Matthew are inserting a common understanding that people in society believed about Jesus (i.e., he’s John the Baptist, back from the dead, and that’s why miraculous powers are at work in him!), then Matthew is at no fault for filling in the story for the reader.

[9] For a fairly brief case for Matthean priority, see David Alan Black, Why Four Gospels? The Historical Origins of the Gospels (Gonzalez, Fl: Energion Publications, 2010).

[10] As far as redacting; adding, omitting, and loosely summarizing were part of the evangelists methods when composing their gospels. This, of course, does not necessarily undermine their historicity. See Carson, Moo, and Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament, 40, 42-45; For a more in-depth process on approaching redaction criticism, see Robert H. Stein, Gospels and Tradition: Studies on Redaction Criticism of the Synoptic Gospels (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, 1991).

[11] Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the wonders performed in you had taken place in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago, in sackcloth and ashes. (Q 10:13) See, James McConkey Robinson, Paul Hoffmann, and John S. Kloppenborg, eds., The Critical Edition of Q: Synopsis Including the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, Mark and Thomas with English, German, and French Translations of Q and Thomas, Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis; Leuven: Fortress Press; Peeters, 2000).

[12] McGrew, Hidden in Plain View, 91.

[13] Carson, Moo, and Morris remind us that, when it comes to the redacting methods of the evangelists, they, “wrote with more than (though not less than) historical interest. They were preachers and teachers, concerned to apply the truths of Jesus’ life and teaching to specific communities in their own day. This theological purpose of the evangelists has sometimes been lost, with a consequent loss of appreciation for the significance and application of the history that the evangelists narrate.” Carson, Moo, Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament, 45.

[14] Solutions to these issues have not been easy. Stein states, “Probably more scholarly time and effort has been spent by New Testament scholars on the solution of the Synoptic Problem than on any other New Testament issue.” Stein, Studying the Synoptic Gospels, 153.

Comments